Home Children Research

Introductory text to come - Sue L.

Introduction

This article describes the history of BIFHSGO’s long-term research project on British home children and the important contribution that Patricia Roberts-Pichette has made over the past 23 years. Patricia has supported BIFHSGO in a number of ways: first as a dedicated volunteer; then as a Board member with responsibility for our research; and latterly as an author, educator, and internationally recognized historian. Patricia has specialized in research on the children who were brought to Canada through the (Middlemore) Children’s Emigration Homes (CEHs). She coordinated the work of volunteers to gather and transcribe data from records and developed the CEH database which, along with its supporting Guide, is in the Name Index. Patricia has also written a number of articles, some of which are featured on our Home Children Research resource page [link pending], and has published a book on the subject. BIFHSGO is grateful to Patricia for this exceptional service to our organization.

Home Children

|

“Home children” is a Canadian term, used to describe more than 100,000 of the very poorest children who were brought from the U.K. to Canada between 1869 and 1948 and settled mainly with rural families in what was known as the assisted juvenile emigration movement. The children, mostly from the slums of British cities and towns, were taken in by about 50 approved, privately-owned juvenile emigration agencies where they received training, health and fitness care before emigration. By 1900 “home children” probably was in everyday Canadian use, but it first appeared in print in The Children’s Homefinder (1913) by Lilian Birt. |

Home Children: BIFHSGO’s first long-term research project

Since the mid-1990s, volunteers of the British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa (BIFHSGO) have been transcribing the names of home children, starting with hand-written documents (until typewritten documents were available) dating from 1869 held at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). In addition, a few volunteers, through background research and by answering the untold numbers of Canadian and world-wide queries, have acquired specialist information about the legal and social backgrounds and experiences these children had before leaving the U.K. and after their arrival in Canada.

David Lorente, the son of a home child and founder of Home Children Canada in 1991 with his wife Kay, both BIFHSGO Hall of Fame recipients (2000), were determined to learn the names of home children brought to Canada and bring their history and stories to the attention of the Canadian public. They first presented their ideas to the Ottawa Branch, Ontario Genealogy Society (OGS) and became known there as the home children champions.

David Lorente, the son of a home child and founder of Home Children Canada in 1991 with his wife Kay, both BIFHSGO Hall of Fame recipients (2000), were determined to learn the names of home children brought to Canada and bring their history and stories to the attention of the Canadian public. They first presented their ideas to the Ottawa Branch, Ontario Genealogy Society (OGS) and became known there as the home children champions.

BIFHSGO, founded in 1994, had many members who were already volunteers at the Church of Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) Family History Center, where they learned the basics of transcribing names for making lists and indexes. The Lorentes put their ideas publicly before BIFHSGO members during the society’s foundation discussions, gave two presentations on home children at its first conference in September 1995, and asked for volunteers. John Sayers, a  long-time volunteer at the LDS Family History Centre and a BIFHSGO Hall of Fame recipient (2001), responded. He soon formed a group of BIFHSGO and OGS volunteers to extract names of home children from shipping manifests held by LAC. The BIFHSGO Board recognized it needed a long-term research focus and because of the research facilities in Ottawa and the enthusiasm of the Lorentes, Sayers and the volunteers already extracting names from shipping records, chose “home children” as its special long-term research project.

long-time volunteer at the LDS Family History Centre and a BIFHSGO Hall of Fame recipient (2001), responded. He soon formed a group of BIFHSGO and OGS volunteers to extract names of home children from shipping manifests held by LAC. The BIFHSGO Board recognized it needed a long-term research focus and because of the research facilities in Ottawa and the enthusiasm of the Lorentes, Sayers and the volunteers already extracting names from shipping records, chose “home children” as its special long-term research project.

An agreement between LAC and BIFHSGO resulted in the extracted names—the initial section of BIFHSGO’s long-term research project on home children—becoming the base of the LAC home children database. The first results (names of home children who arrived in Canada during 1870) were published in Anglo-Celtic Roots, Volume 3, Number 3, 1997. BIFHSGO’s work ended on this section of the project when names of home children had been extracted from the manifests of all incoming British ships in the LAC collection between 1869 to 1935 (the last year in LAC’s collection). Today LAC continues to add information to this database and BIFHSGO volunteers continue extracting information on home children from other federal government records.

The Children’s Emigration Homes

In 1993 the records of the Children’s Emigration Homes (CEH)—an assisted juvenile emigration home founded in 1872 by John Throgmorton Middlemore of Birmingham, U.K.—were microfilmed on behalf of the Australian Joint Copying Project and the National Archives of Canada (now LAC) with the kind permission of the Middlemore Trust, Birmingham, England. The Australian share of the microfilms is archived at the Australian National Library, while the Canadian share of the microfilms, about 120 reels, is archived at LAC as “Collection MG28-I492, the Middlemore Children’s Emigration Homes fonds.”

The second part of BIFHSGO’s long-term home children project was started in 2001 with the extraction of CEH children’s names and records from LAC Collection MG28-I492. In the early 2000s the Middlemore Trust deposited the CEH records in a public archive in Birmingham now known as the Wolfson Centre, the only assisted juvenile emigration agency to take this action.

Middlemore considered that expatriation was too strong a remedy for cases of ordinary misfortune and only accepted the very worst cases. With his staff, and after the training and medical care of children taken into the CEH (most under 14 years of age), in 1873 Middlemore brought his first party of children to Canada for settlement from temporary receiving homes in Toronto and London. In 1893 Middlemore made the Maritime provinces his only settlement area.

Children’s Emigration Homes Records: indexing project

In early 2001, the LAC Collection MG28-I492 documents over 100 years old were opened to the public. When this was brought to BIFHSGO’s attention, long-time BIFGHSO volunteer and Hall of Fame recipient (2007), Dr. Patricia Roberts-Pichette volunteered with about 60 BIFHSGO volunteers and friends to extract the names and references of CEH children settled in Canada from 93 reels of the 120-reel LAC collection, and from documents not part of that collection—a total of 12 different files. This project started in 2001 and is ongoing.

In early 2001, the LAC Collection MG28-I492 documents over 100 years old were opened to the public. When this was brought to BIFHSGO’s attention, long-time BIFGHSO volunteer and Hall of Fame recipient (2007), Dr. Patricia Roberts-Pichette volunteered with about 60 BIFHSGO volunteers and friends to extract the names and references of CEH children settled in Canada from 93 reels of the 120-reel LAC collection, and from documents not part of that collection—a total of 12 different files. This project started in 2001 and is ongoing.

Middlemore’s CEH: the work of Dr. Patricia Roberts-Pichette

In March 2002 the nominal index for CEH children emigrated to Canada between 1873 and 1880 appeared on the BIFHSGO website and was completed when the names of children sent abroad each year until May 1932 were added (the last year the CEH send children to the colonies). The CEH brought approximately 5,200 children to Canada. With all the children’s names extracted, Roberts-Pichette completed a nominal index on the BIFHSGO website in 2003. About 2019 Roberts-Pichette added the references for each child on the nominal index, creating the Name and Reference Index of the Children’s (Middlemore) Emigration Homes and Its Sources, or CEH Index that now forms part of BIFHSGO’s Name Index. She has also produced a comprehensive Research Guide to Children’s (Middlemore) Emigration Homes Index that describes the contents of the 12 files, tips on solving problems and locations where the references may be seen or copies obtained. Sparked by this work, Roberts-Pichette has gained a unique perspective on the work of the CEH from the unlimited access she had to all relevant CEH files up to 1941 and to personal communications with Middlemore family members, home children, and descendants of CEH children.

In her comprehensive book, which evolved from her research, Great Canadian Expectations: The Middlemore Experience (2016), Roberts-Pichette revealed that the experiences of CEH children were mainly positive and that most thrived in Canada. She also considers that, contrary to current popular opinion, the experiences of the children from the well-known assisted juvenile emigration agencies were similar.

According to Charlene Elgee, Roberts-Pichette reviewed “the legal framework [of the assisted juvenile emigration movement], contemporary social movements like eugenics, political movements and reactions, the prejudices and backlashes against immigrants, the social climate of both the U.K. and Canada at the time, the effects of the Great War, and the evolution of the relationship between the British government and its colonies.” (See Canadian Immigration Historical Society, Bulletin 82, September 2017, pages 15-16). Taken together with what she learned from the CEH and other records, Roberts-Pichette concluded that John T. Middlemore’s motivations were truly altruistic and, compared with late 1800s’ and early 1900s’ contemporary social practices, he was far ahead of his time. For further information on Middlemore and his children's emigration homes, more information will be available on the “Resources” tab under “Home Children Research” shortly.

About Home Children in Canada

by Patricia Roberts-Pichette

Introduction 1

Backgrounds of Home Children Brought to Canada 2

Juvenile Emigration Homes 4

Responsibilities of Juvenile Emigration Agencies in Canada 6

Visiting Home Children Settled in Canada 6

Union Workhouses 7

Reformatories and Industrial Schools 8

End of the Assisted Juvenile Emigration Movement in Canada 9

Explanation of Terms 9

Resources 13

Introduction

The British Isles have had a long history of child migration to former colonies. Some children certainly arrived in Canada before Confederation in 1867, but this paper is about the estimated 100,000 or more whom Canadians now call “home children,” who were brought and settled in Canada between 1869 and 1948 under the assisted juvenile emigration movement. These young people, under the age of 18 years and perhaps as young as 12 months (but most were probably at least 7 years old and less than 14) were brought mainly to Ontario by approved British juvenile emigration agencies. Children under 14 years of age were said to be adopted, but Ontario did not have a formal adoption law until 1921. It is often said that the children were brought over as cheap labour, but that is open to question. Most home children were of school age and were required by provincial laws to attend school—they did not receive wages until they left school (usually at 14)—yet by their mid-twenties, many boys were married, were able to buy farms, build their own homes or become business partners with their settlement families in such businesses as the family farm, the country store or the timber mill.

Most boys learned skills related to farming and girls learned skills related to home management. In this way, by adulthood, boys would have learned practical farming skills or the basics of a useful trade, and the girls would have learned the arts and science of practical home management and other skills needed by all women. The settlement families of some children paid their secondary school fees (it was not free in those days) or even part of post-secondary training, for which these young men and women may have won scholarships and contributed from their own savings to become ministers of the church, nurses, secretaries, or teachers. Many settlement families paid for organ or piano lessons for the girls settled with them. Other young people apprenticed themselves for training in such trades as carpentry, dressmaking, machinery repair, millinery and telegraphy or, with post-secondary training, went into business for themselves.

Canada was anxious to increase its population and welcomed this assisted juvenile emigration movement as a nation-building exercise. The children would grow up as Canadians knowing Canadian culture and would require less training in adulthood than adult immigrants. It was also seen, in part, as an altruistic movement for those Canadian families whose children had left home―empty-nesters who missed the sound of children in their homes—or for families who wanted children but had none of their own. The movement was often described as saving the British public purse by reducing the cost of operating workhouses, but this is controversial, as once parties of children had left for Canada there were always more poor neglected children to fill the vacant spaces.

“Home children” is a Canadian term, probably in everyday use since the early 1900s. However, it was rarely, if ever, used in newspapers, where juvenile immigrants were commonly referred to by the name of their sponsoring agency, perhaps as “British youth,” or often carelessly as a “Barnardo boy or girl” (most often not the case). As far as is known, the term was first used in print in The Children’s Home-Finder: The Story of Annie Macpherson and Louisa Birt, 1913, by Lillian M. Birt, pages 145 and 186. The term also appears in the 1924 Bondfield Report, commissioned by the British government to investigate the condition of the British juvenile emigrants settled in Canada. The report noted that “home child” was regularly used in Canada, although some settlement families disliked it, and commented:

“We did not find it was used in any derogatory sense, and so far as we could ascertain, there was no prejudice against these children.”

By comparison, they found discrimination against the Children’s Aid Society’s children, who were commonly called “shelter children.” Unlike most families who took juvenile immigrants, families who took Children’s Aid Society children were paid to do so. Dr. Barnardo’s agency was an exception. In the 1890s, Barnardo’s paid families who took young children, but the payments stopped when the child turned 10 or 11; often the child was returned to the agency for resettlement and a younger child requested.

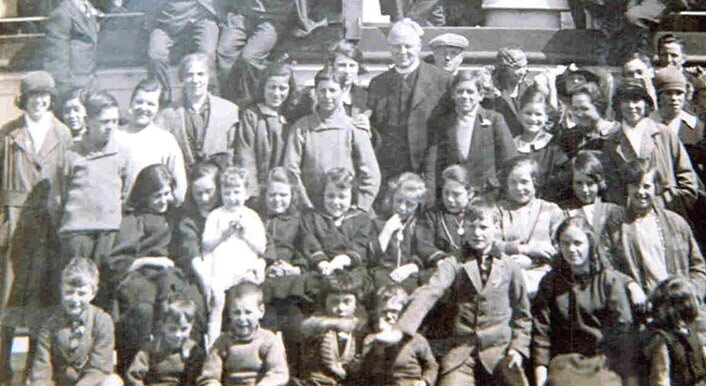

Backgrounds of Home Children Brought to Canada

British children destined for Canada were inevitably poor (but not as poor as paupers who were inhabitants of workhouses), undernourished, hungry, often neglected, cruelly treated, and usually covered in vermin when they were admitted to an emigration agency’s receiving home in Britain. By the time they were ready to leave the home for Canada they had received medical and dental attention, good food, new clothes, and social training, so that when they boarded the ship most groups looked very much like any well-groomed group of British school children of the period.

In Canada most people thought these children were orphans, but this was because in Britain at the time, children whose father had died or deserted them were often called orphans. Probably less than five per cent of home children were true orphans.

Most home children came from the poorest working-class families who lived in the worst slums of the great industrial cities. Their families were living in or had fallen into abject poverty because of job loss, illness, incapacity, or death of the breadwinner. Many youths were on their own, having been deserted by one or both parents. The lack of money and public social service supports often drove a deserted or widowed mother lacking support from family or friends to the workhouse or to prostitution. Some mothers in these latter circumstances introduced their preteen daughters into the trade. Many deserted and widowed fathers, with young children and no close relatives who could help with their care, as a last resort took their children to an emigration agency’s receiving home, normally giving permission for their children to go to Canada and often agreeing to pay for their support until they were settled in new homes.

Beginning in the 1770s, British churches often provided working children with free schooling on Sundays and a free meal to attract them. By the early 1800s, people were noticing that there were more poor and hungry children on the streets, often described as “running the streets.” Social activists, church and civic officials viewed them as being in danger of adopting delinquent behaviours just to feed themselves and thus becoming criminals. By 1831 it was reported that children’s attendance at the Sunday schools for free schooling had grown to 1.2 million. Attendance at these schools in 1860s Birmingham was recorded as sporadic and, for most working-class children, education was over by the age of 10. Records for other industrial towns and cities were probably similar.

Most Anglican churches had some means of providing small amounts of money and/or food (usually bread) to destitute families born in the parish, but those born in a parish other than where they were living were not assisted. Many of the Nonconformist churches, however, had mission rooms where, whatever their beliefs, children found on the street late at night were taken to eat and sleep. At first, the only available government support was the workhouse, which most people tried to avoid at all costs because of their deliberately sanctioned draconian rules. Most poor women had their babies in a workhouse hospital.

Economic depression developed in Britain during the 1870s and lasted into the 1890s. Primary schooling for all children from their fifth to their twelfth birthdays was introduced in 1870. Parents were legally responsible to see that their children attended, but state schools did not become free until 1891. Hungry and starving children were still on the streets when they should have been in school and were therefore legally truants. They spent their school money to buy food or, without it, did as all hungry working-class children had always done―supported themselves by begging from people on the street, petty theft of handkerchiefs and other small items to sell, or by stealing foodstuffs from market stalls. Sometimes they earned a few pennies by holding a horse, delivering a message, or doing some other small service such as selling flowers or matches. The parents or guardians of these children, and even the children themselves, were liable for prosecution before a magistrate for truancy.

In 1889, the British law against child cruelty authorized the newly founded National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children to bring cases of cruelty and neglect to the notice of the police for prosecution of the parents or guardians. When a magistrate found the parents or guardians guilty and sentenced them to imprisonment, and he believed the children were in physical and moral danger, he could order them to a “place of safety” (municipally certified homes of various types) or make other arrangement for the children while their parents or guardians served their sentences. Newspaper reports about these cases described the children as dressed in rags, dirty, hungry, or starving, and covered in vermin. These children had probably never seen a bathtub, let alone been in one, but their hands and faces were probably wiped occasionally with a damp cloth.

Descriptions of the homes of the poorest slum dwellers reveal that they were often awful beyond belief. Sometimes it was just a single room. If it was a terraced back-to-back house, it rarely had more than two rooms and an attic above the ground floor with one room per floor, one of which may have been rented to a lodger and shared with a family member. These terraces surrounded or partly surrounded a central court. The houses did not have bathrooms: privies (toilets) were separate buildings outside the house in the court and were used by multiple families. All water had to be carried inside from an outdoor standpipe attached to a well or water supply. People trying to help the children would often be driven away from such homes by the filth and stench.

The housing architecture for the working class started to change late in the 1800s. New houses may still have been terraced but opened both to the street and the court, allowing for much better ventilation. There were usually two rooms to a floor instead of one, with larger windows for increased air circulation; a bathroom was included, and water was piped in. Many old houses were updated with the insertion of bay windows and piped water to the kitchen sink. Construction and updating programs were slow and interrupted by two world wars and the Great Depression—the effort was not completed until well after the Second World War.

Juvenile Emigration Homes

In 1869, Maria Rye was the first person to bring a party of children—known as assisted juvenile emigrants—to her home “Our Western Home” in Niagara-on -the Lake, Ontario. Next to arrive with a party for Ontario was Annie Macpherson in 1870; her first home “Marchmont” was in Belleville. They were soon followed by newly founded juvenile emigration agencies led by Louisa Birt, John T. Middlemore, and Thomas Stephenson, who brought children not only for settlement in Ontario, but also by 1872, for settlement in Québec and Nova Scotia. It was not until 1885 that a party was settled in New Brunswick. In 1886, Emma Stirling opened a home in Nova Scotia while in 1888 Thomas Barnardo, who already had a home in Ontario, opened a second one in Manitoba. Each juvenile emigration agency’s receiving home in Britain and distributing home in Canada was privately owned by an individual or a philanthropic society.

Children were brought by the agency from its British receiving home to its distributing home in Canada, from which they were soon settled and to which they could return if the settlement was unsatisfactory. These homes in Britain and Canada were supported primarily by private subscriptions, donations, or legacies from British sources. Many were affiliated with specific churches (e.g., the Waifs and Strays Society was the Church of England agency); others had no specific church affiliations but nevertheless were supported by a variety of churches and religious organizations. The homes in Britain were not subsidized by the British government, but the municipal councils where they were located often assisted in various ways. In Canada the distributing homes were mainly supported by the British agency. Despite this, in the localities where they were situated, the agencies often received support from local residents and the municipality, and sometimes from the province. Many of the agencies, including those of Macpherson, Rye and Middlemore, often included union workhouse children, children from industrial schools and reformatories, or privately sponsored children in their parties for Canadian settlement. These children, particularly those from large workhouses, may have spent several years there before joining a juvenile migration agency’s party, unlike the emigration agency’s children, who generally spent a relatively short time in the agency home. Consequently, the children from workhouses may have had a more challenging time adapting to Canadian conditions. The sponsor of children not trained in the juvenile emigration agency's British receiving home, whether an individual or organization, had to cover the costs of travel, clothing and inspection visits, and usually provided the name of a contact person in Canada. Some emigration agencies include overaged (18 years or older) young persons in their parties to accompany younger siblings. Sometimes the agency found a position for them in Canada but bore no other responsibility for them.

On admission to an agency’s home, children usually had flea bites on their bodies, and many had scabies itch, boils or sores. Their hair was usually full of lice and their heads often had ringworm. For these reasons children were immediately given a bath on admission, their heads shaved, and their clothes burned and replaced with new, clean ones. Many were sick (e.g., measles, chickenpox, fevers, tuberculosis), requiring isolation in the home or hospitalization to recover before being allowed to mix with the other children in the home.

While in a receiving home, children were prepared for their emigration and the life they were likely to live in Canada. Most emigration agencies tried to prevent children from becoming “institutionalized” by keeping them for less than about 11 months before emigration, and many children were there for only a few weeks or days before emigration.

Besides going to school and church, whether those facilities were in-house or outside the home, their basic training in the receiving homes was mostly social. It focused on how to look after themselves: the development of self-respect, good manners, cleanliness, and honesty, what service meant, the importance of obedience and personal responsibility, and perhaps some basic understanding of care for animals, gardens, and homes. Street smarts learned in urban slums were not appreciated and of little use in Canadian rural districts.

Juvenile emigration homes in Britain were in urban areas with little access to large open spaces, but visits to a farm or an agricultural exhibition were possible. Further, most agency homes had small gardens and perhaps pets, both of which gave children the opportunity to learn lessons of responsibility in meeting the needs of other living things. Some homes even had specialists bring in animals, perhaps a cow, to explain how it was milked and looked after. More detailed agricultural training would not necessarily have been of much help because of the ages of the children and the difference between Canadian and British weather and farming adaptations.

At least a few of the juvenile emigration agencies sent their children to the state schools and to the local churches and Sunday schools. They also provided opportunities for the children to attend such events as concerts, fairs, and picnics, where they met outside people and practised the social skills they were being taught. The perception of some was that children with such experience outside the walls of their agency would adapt more quickly to life in Canada than those children from workhouses and orphanages who did not have such experiences.

With reading, writing, and arithmetic learned at school, the social skills learned in the homes and a knowledge of what responsibility meant, children aged 14 or older when they arrived in Canada, were ready to learn and practice the skills to be taught by the settlement family. Most settlement families signed a document that clearly stated they were responsible to teach their immigrant children or have them taught a trade or skills necessary for becoming a productive and self-sustaining adult. The settlement farmer (usually called “Master” or “Mr.” by older boys) would teach a boy the skills needed to farm, look after animals and crops, and repair broken equipment, while the girls would learn the skills of home management, cooking and sewing from the farmer's wife (usually called “Mistress” or “Mrs.” by older girls). Many girls were also taught to play the piano or organ. The skills for living were not taught in Canadian schools, where reading, writing and arithmetic were the main subjects. Younger children usually called their foster parents "Mama" and "Papa."

Responsibilities of Juvenile Emigration Agencies in Canada

Juvenile emigration agencies, as legal guardians, took responsibility for the children they settled in Canada until they reached their 21st birthday unless provincial law changed the age. This included visiting them once a year at least and reporting on their progress. If there were difficulties they were responsible for settling things between the child and the settlement family, although, given that some of the children were indentured, this may have been difficult and requiring the intervention of magistrates, especially if teenaged boys ran away, were found and returned to the settlement family. If young people married before age 21, they were considered to have come of age and were no longer the responsibility of the agency. If the young person was female, she became the responsibility of her husband. In 1897 Ontario made the agencies legally responsible for their children until their eighteenth birthday.

Visiting Home Children Settled in Canada

The agencies’ representatives (Canadian or British) made annual visits to the homes of all their children until they reached their eighteenth birthdays unless a province required a different visitor cut-off time. If there were problems, some agencies visited their children for a longer period. In Ontario, however, agencies were not required to visit their children after the age of 16.

Starting in 1883, Canadian federal inspectors were required to make annual visits and report on the progress of all workhouse children settled by the assisted juvenile emigration agencies. These reports were sent on to the boards of guardians of the workhouses from which the children had come. Most of the agencies who settled workhouse children also visited them and sent their reports to the respective boards of guardians. Sometimes the two reports did not agree. In such cases, the board of guardians contacted the agency’s headquarters in Britain to request an explanation of the difference. The request was passed on to the agency’s superintendent in Canada for an explanation, with instructions to take any necessary action and report back on results so the board of guardians could be informed.

In 1920, Canada extended the duties of the federal inspectors to visiting all assisted juvenile immigrants until their eighteenth birthday. If the federal inspector found difficulties with an emigration agency child, discussions were held with the agency’s Canadian superintendent to resolve the difficulty. The superintendent then reported the resolution to the agency’s headquarters in Britain.

Union Workhouses

As mentioned earlier, in Britain, “pauper” was a technical term used for all union workhouse residents or receivers of Poor Law relief. Street people, although poor, were not in the British sense “paupers” i.e., the very poorest. This distinction was not recognized in Canada where the term “pauper” was used for all poor people and most often in a derogatory sense.

The workhouse was a long-standing British institution, set up by a local parish to care for the poor. The British Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, in response to the fact that most parish workhouses were too small to accommodate the steadily increasing numbers of indigent poor, called for the grouping of adjacent parishes into a union, the building of single large workhouses to serve the union parishes, and the closure of all the small parish workhouses. Although officially these large workhouses were called “union workhouses,” the terms “union” or “workhouse” were, and still are, used as synonyms. Each union workhouse was tax supported, was governed by a board of guardians elected by members of the involved parishes and was overseen by the Poor Law Commission. All workhouses after 1834 had to employ a schoolmaster or schoolmistress to provide their children with three hours of education daily.

By the mid-1800s, union workhouses were overcrowded with poor and orphaned children, and partly to solve the problem, the 1850 Emigration of Children Act included a section on the emigration of pauper (i.e., workhouse) children, (union workhouses, as state-supported institutions, could not send their own children abroad). The Act permitted the assisted emigration of workhouse children to the colonies, but the lack of any intermediary bodies—agencies or organizations established to transport and settle emigrant children—meant that few workhouse children were sent abroad for nearly 20 years. The first agency to meet the criteria was that of Maria Rye, who in 1869 included some workhouse children in her party of children for settlement in Ontario, Canada. The second one was Annie Macpherson, who included workhouse children in her 1870 party, also destined for Ontario. Not all juvenile emigration agencies agreed to take and settle workhouse children in Canada.

The British Elementary Education Act of 1870 required all children to attend school full-time from their fifth to twelfth birthdays. Most workhouses had their own schools; few workhouse children attended state schools. The settlement of workhouse children in Canada started in 1869 but was stopped in 1875 following the publication of the Doyle Report. Andrew Doyle had been commissioned by the British government in 1874 to inspect the treatment of workhouse children settled in Canada. Doyle’s report was highly critical of the way Macpherson and Rye monitored the children they settled in Ontario and Québec.

In 1883, after an agreement was reached between the Canada Department of Agriculture (then responsible for immigration) and the British Local Government Board (later replaced by the Poor Law Commission), which was responsible for the administration of Poor Laws, some juvenile emigration agencies resumed the emigration of workhouse children under the agreed conditions. Among these conditions were annual visits and reports by Canadian federal government inspectors to settled workhouse children to report on the progress they were making. These reports were sent to the boards of guardians and passed on to the Local Government Board. Copies were kept in Canada. Although it was not universal, most boys from workhouses were usually between the ages of 14 and 17, while girls, who were supposed to be under 10 years of age, were most often older.

When taken into a workhouse, families were separated by sex and age from the age of 2, although a child under 7 could, if it was deemed “expedient,” be accommodated in his or her mother’s section and usually shared her bed. Limited daily appointments could be set up for parents to visit their children. The main advantage of workhouses was that inmates received three meals a day (even if of a very poor quality by today’s standards), a place to sleep, and access to medical facilities. All able-bodied people were put to work, most often stone-breaking for men, while women picked apart old rope to produce oakum, used for caulking ships. Children started work when they reached the age of 14.

Workhouses had their own chapels and schools, so children rarely, if ever, left the grounds; they only mixed with others like themselves. Some union workhouses set up “villages” of “cottage homes” quite separate from the main union building, where groups of 15 to 25 children lived in separate cottages (two-storied houses) each with a resident married couple as “parents.” The school and chapel were also part of the village, and usually there were workshops for teaching the children various skills. The Marston Green Cottage Homes in Birmingham were an early example. The Quarrier Home at Bridge of Weir in Scotland (both an orphanage and a private juvenile emigration receiving home) was organized in a similar way.

Reformatories and Industrial Schools

These were training institutions for children who had been in trouble with the authorities: reformatories for children who had been in jail and industrial schools for children who had not been in jail. The children in both institutions usually received training in trades such as agriculture, woodworking, shoe repair or metalworking, so that on release at the age of 16 or 18 they would have some way of making a living. By today’s standards their transgressions were minor: stealing a handkerchief, stealing from the market, begging in the street, being homeless and without any means of support, or being in the company of reputed thieves. A first or second court appearance without a jail sentence could land a child in an industrial school, especially if under 14 years of age. Several court appearances could result in a jail sentence of about a week and then transfer to a reformatory until their eighteenth birthday. The number of these children brought to Canada and settled by the juvenile emigration agencies was small. As far as can be determined, no reformatory children were brought to Canada after 1893.

End of the Assisted Juvenile Emigration Movement in Canada

All Canadian federal support for juvenile emigrants stopped in mid-1932, because of the Great Depression. This did not stop juvenile emigration to Canada, but severely reduced it. After the Second World War and again anxious to increase its population, Canada reintroduced support for immigrants. As far as can be determined, the Fairbridge Society brought the last party of assisted juvenile emigrants to Canada in 1948 to its Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School in British Columbia.

Explanation of Terms

Adoption: Laws for adoption were a provincial responsibility. Adoption is a legal process where minor persons become the lawful children of persons who are not their natural parents. The minor persons have the same inheritance rights as children born to those persons. Ontario, for example, did not have an adoption law until 1921. Until 1921, adoption in Ontario could be familial (i.e., informal agreements made between families or friends, or between the emigration agency and the settlement family, just as happened in Britain) or vary rarely by statute (i.e., Act of the Provincial Legislature). In Ontario, where about 70 per cent were settled, most home children had familial adoptions, but some were indentured to the settlement family based on Ontario’s 1851 Act Respecting Apprentices and Minors and its subsequent amendments. This made the settlement families guardians of their home children, not adoptive parents. (See Guardianship below.)

Age classification of children and young persons: Young people were generally classified into three groups by the British and Canadian federal governments. The provinces sometimes used the same classification system but were more likely to have used their own specific age group names:

- a child was under 14 years of age

- a youth was 14 years of age and under the age of 18

- a [young] adult was 18 years of age and under the age of 21, but without the rights and responsibilities of an adult

- an adult was 21 years old, having reached the “age of majority” or become “of age” on their 21st birthday with the full legal rights and responsibilities of an adult of the time. (In 1970, Canada reduced the age of majority from 21 to 18.)

There is sometimes confusion when interpreting what is meant by an age range used for classification purposes. A group of youths might be described as “aged 14 to 18”―does this mean that the oldest was 17 or 18 years old? Juvenile emigration agencies could only receive the Canadian government bonus for children under the age of 18. Thus, in this context, “aged 14 to 18” means from the child’s fourteenth to eighteenth birthdays.

Board of Guardians (U.K.): The local committee responsible for the governance of a workhouse Union

Canadian citizenship: In the Immigration Act of 1910 a Canadian citizen was defined in three ways:

- as a person born in Canada

- a British subject domiciled in Canada, or

- a British subject naturalized under Canadian law

Canadian passports: Canadian passports were not introduced until after the Second World War—before that time Canadians were "British subjects resident in Canada" (as all home children became after their requisite domicile in Canada). After the First World War, like all members of the Empire, Canadians carried a British passport, which had on the top of the outside cover “British Passport,” then the Canadian Coat of Arms centred, beneath which was “Canada.” Assisted juvenile emigrants travelling to Canada travelling on British or Canadian ships did not carry passports or identification papers.

Home children in Canada who wanted to go to the U.S.A. with their settlement families (or on their own once they were beyond care) carried not a passport but an officially stamped letter or form, normally signed by the Governor General. In 1915, this document was replaced by the British booklet passport.

Canadian travel subsidies, capitation fees, bonuses, and age restrictions for assisted immigrants: After Confederation, Canada was anxious to increase its population as quickly as possible to develop its resources and protect it from possible takeover by the U.S.A., so the federal government instituted subsidies and other inducements to attract British immigrants. It subsidized both shipping costs from Britain to Canada and train travel from the port of entry to localities in Québec and Ontario, as well as sometimes reimbursing the capitation fee of $2 charged to each immigrant. If the immigrants were travelling in a group sponsored by an emigration agency, the party leader paid the capitation fees to the captain of the ship, who, on arrival at the Canadian port of entry, handed the money to an immigration official before the party was allowed to disembark. After checking that the specially listed passengers were all bona fide immigrants, the government later returned the capitation fee to the sponsoring agency.

After some parliamentary wrangling on immigration policy in 1888, the federal government cancelled the assisted passage policy for immigrants, even though Canada was still vigorously competing with Australia and the U.S.A. (and their inducements) for British immigrants. It did, however, begin providing juvenile emigration agencies with a $2 bonus for each child under 18 years of age brought to Canada, except for workhouse children. The actual cost of travel and clothing for an assisted immigrant child coming to Canada until 1916 was about £16, equivalent then to about $64 Canadian. This cost was paid by the agency bringing the child.

Travel costs after the First World War were about 3.5 times higher than before the war. In response to the agencies' higher costs and with the hope of increasing the numbers of juvenile immigrants, Canada in 1920 abolished the $2 bonus, replacing it with an annual $1,000 grant for any agency settling at least 100 children each year in the hope that the numbers of juvenile immigrants would increase. This changed again under the Empire Settlement Act of 1922, when the British and Canadian governments, in a bilateral agreement, agreed to share the travel costs of all assisted juvenile emigrants from their U.K. receiving homes to the homes of Canadian settlement families.

In 1925, following the publication of the 1924 Bondfield Report that examined the success in Canada of assisted juvenile immigrants from the U.K., British law specified that only children who had completed their primary education in the British Isles and were at least 14 years old and under 18 years of age (their seventeenth birthday could not be earlier than the year in which they emigrated) could receive the British and Canadian support for travel under the Empire Settlement Act bilateral agreement. Nevertheless, when one province in 1927 asked for younger children, Canada granted permission, provided the agency paid all expenses associated with such emigration. In 1929 there was another change: Canadian officials in Britain denied emigration to Canada of juvenile emigrant boys aged 14 who were less than five feet tall.

Colonial Office (U.K.): Department dealing with British overseas possessions except for India

Domicile was defined by the number of years a person was resident in Canada. By the 1910 law, to become a Canadian citizen you had to be domiciled in Canada for three years, but in 1919 an amendment extended the domicile term to five years and included a list of prohibitions that denied citizenship.

Education (British): The U.K. Elementary Education Act of 1870 set up requirements for state schools in England and Wales for children aged 5 to 13. Scotland passed similar laws in 1872. All children were legally required to attend primary school, but depending on the local school boards’ decisions, especially in the poorest areas, the poorest children usually left school at age 10 to find work and help support the family. At first, primary education at state schools was not free, but it became so in 1891. Various changes were made to the school leaving age―it first went down to age 10 then went gradually upwards again. At the end of the First World War school leaving age was legally confirmed at age 14. This did not mean that children had to stop going to school on the day they reached the prescribed leaving age; they could continue at school if they wished.

Education (Canadian): In Canada, education laws varied from province to province, with most not requiring full-time school attendance until 1900 or even later. Ontario, for example, in 1871 became the first province to institute a compulsory four months of primary school education annually for all children, whether Canadian-born or immigrant, from their seventh to thirteenth birthdays. In 1891, Ontario implemented full-time attendance for all children between their eighth and fourteenth birthdays. There were various provisions to excuse non-attendance: e.g., lack of a school or schoolteacher, or the distance from the home to the school being greater than that prescribed by law. If the settlement family kept their home child in school full time past the prescribed leaving age and provided food, clothing, laundry and pocket money, the child did not receive wages until after she/he had left school.

Feeble-minded or mental defective: A catchall, not clinical, term for people on the margins of society whose very existence was believed to undermine the harmony of society. For example: under-achievers, runaways, truants, unwed-mothers, children from broken homes, and the mentally challenged.

Guardianship: Guardianship is a legal process whereby minor persons under the age of 21 become the wards of people who are not their natural parents. The guardians are legally responsible for the minor persons (including home children) until adulthood, but they do not legally become part of the family, (they do not have the right to the family name or to any inheritance). Please note: Many early Ontario guardianship records include the word “adoption” in error.

Home children: In the strict sense, home children were under the age of 18 when admitted to a juvenile emigration agency’s receiving home in Britain for training before being taken to its distributing home in Canada. From this distributing home they were settled with interviewed families. The children could return to their distributing home if necessary.

By common usage, but inaccurately, the term “home child” is sometimes expanded to include any child or young person who came to Canada unaccompanied by his or her parents. The emigration parties of some agencies included over-aged young persons (i.e., 18 or older), most of whom were not given settlement assistance. These young persons were not home children and the agencies who brought them were ineligible for the federal bonus or other support for juvenile immigrants.

Local Government Board (U.K.): The government body that managed the Poor Law

Overseas Settlement Committee (U.K.): Office within the Colonial Office dealing with emigration

Paupers, guttersnipes, street arabs, and waifs and strays: In Britain, these terms were used for two distinctly different groups.

- “Pauper” applied only to the poorest adults and children who were currently or had been in a workhouse or received Poor Law assistance. It was a technical term and not a term of disparagement. Paupers were families at the lowest level of the working class and needed state help to survive.

- “Waifs and strays,” “gutter snipes and “street arabs” were disparaging terms for children who had never been in a workhouse. They were often described as “running the streets” and being out of parental control. Their families were poor but not as poor as paupers.

In Canada, no distinction was made in the use of these terms―they all were terms of disparagement—usually directed at home children but also to poor Canadian children found “running the streets” in Toronto.

Resources

Archives of Ontario https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/ https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/access/documents/research_guide_223_guardianship_and_adoption.pdf

BIFHSGO British Home Children: Their Stories (Carleton Place, ON: Global Heritage Press, 2010)

Birt, Lilian M., The Children’s Home Finder: The Story of Annie MacPherson and Louisa Birt (London: J. Nisbett and Company, 1913)

Bondfield, Margaret Grace, Report to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, President of the Oversea Settlement Committee, from the Delegation appointed to obtain information the situation of child migration and settlement in Canada (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1924). LAC reel 76, vol. 67, file 3115, part 16

British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

Doyle, Andrew, Emigration of Pauper Children to Canada, Report to the Right Honourable the President of the Local Government Board (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1875). Please note that “Pauper” in this report means children from workhouses. For a free online copy see Canadiana: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_05950/2 .

Fairbridge Society: https://www.princes-trust.org.uk/about-us/research-policies-reports/fairbridge-society

Kohli, Marjorie, The Golden Bridge: Young Immigrants to Canada 1833–1939 (2003) Natural Heritage/Natural History Inc. P.O. Box 95, Station O, Toronto, ON, M4A 2M8

Lane, John, Fairbridge Kid (Freemantle, Australia: Freemantle Arts Centre Press, 1990). This is the autobiography of a Fairbridge child who was originally a Barnardo child. It is well worth reading by anyone interested in British home children wherever they were settled. (Available from AbeBooks.) A copy is at the Ottawa City Archives (OGS Collection).

Library and Archives Canada, 395 Wellington Street, Ottawa ON, K1A 0N4, CANADA

Tel. 613-996-5115

Fax 613-992-5921

Email: reproduction@bac-lac.gc.ca

Roberts-Pichette, Patricia, Great Canadian Expectations: The Middlemore Experience (2016) GlobalHeritagePress.ca https://globalgenealogy.com/

Email: sandra@globalgenealogy.com or rick@globalgenealogy.com

Wolfson Centre, Centenary Square, Broad Street, Birmingham, B1 2ND, U.K.

Email: archives.heritage@birmingham.gov.uk

archives.appointments@birmingham.gov.uk

BIFHSGO has developed an index of Children’s (Middlemore) Emigration Homes. Although none of the Middlemore source documents are available online, researchers can request access to or obtain copies of documents from microfilm reels held at Library and Archives Canada, the Library of Birmingham or the National Archives of Australia. Learn more about the Children’s (Middlemore) Emigration Homes initiative and the .J. T. Middlemore’s Agency.

Learn more about instructions on how to order or access copies or records, and a description of the records themselves, in the Guide to Children's (Middlemore) Emigration Homes Index.

In addition, there are two subject indexes:

- Contents and Notes [pending] for the CEH (Middlemore) Annual Reports (1872/3–1939)

- Index to the Gerow, F. A. report for 1905 on the Middlemore Home, Fairview Station, Nova Scotia

Children’s Emigration Homes (Middlemore) : Indexing Project and Acknowledgements [this text could be in the main body of the dropdown - or is it duplicated with other Middlemore texts?]

[What is this and where does it fit? Contents and Background of Frank A. Gerow’s Report on the Middlemore Home, Fairview Station, Nova Scotia]